What will become of the generation of Syrian children that has grown up knowing nothing but war? As the con ict grinds into its sixth year, some three million children have been displaced from their homes, while another half a million are living under siege conditions, with no access to humanitarian aid. Those who have managed to ee the country remain traumatised by what they have experienced.

According to a new report commissioned by Save the Children, conducted across seven of Syria’s 14 governorates, many children are su ering from “toxic stress”: a state of mental distress that manifests itself in insomnia, nightmares, bed-wetting, speech impediments, self-harm and increased aggression.

Mohammed. Eight.

In the year after he saw his father’s body laid out at the mosque, the victim of a sniper’s bullet, Mohammed would often refuse to speak. His mother remembers watching him playing in the corner, unreachable. When he started to talk again, he had acquired a profound stammer. “I’m afraid at night when there’s no one in the street,” he told Ahmad Baroudi, who interviewed him at the Turkish residential centre where he now lives. His mother worries that he is becoming increasingly aggressive and uncontrollable. “I get upset when I am playing and someone comes and ruins the game,” he said. “When I get upset, my heart feels like it is falling down. My head becomes hot and my hands get numb.” He longs for the war to end. “I would love to go back to Syria to defend my homeland. I would like to live a good life where there is grass around us and a river next to us, and lots of birds.”

Ahmed. Nine.

In the tumultuous days after his father’s death, Ahmed and one of his sisters were separated from their mother. They ended up tagging along with a relative who led them to a bleak place of refuge: the Isis-controlled city of Raqqa. There the siblings saw dead bodies, heads on spikes and public lashings. Ahmed began wetting the bed and, although he has shown signs of psychological improvement since being reunited with his mother in Turkey, he only sleeps for a few hours a night. “I am afraid of blood, and I am afraid to see a dead body and someone with his head chopped off,” he told Baroudi. “I have new friends here who I play with but I am very sad when I am alone.”

Hassan. Nine.

It took Hassan and his mother eight months to escape from Syria into Turkey. Hassan had already witnessed his father’s death – shot at close range by fighters who had broken into their home – and that of his sister, who died from the burns she received while trying to light a stove as the family sheltered for the winter in temporary accommodation. Today, he is an introverted child, afraid of the dark but prone to outbursts of violence. “I dream of a big bird, bigger than me, that I can ride and fly away,” he told Baroudi. “I dream that I can fly, fly fast away into the sky.”

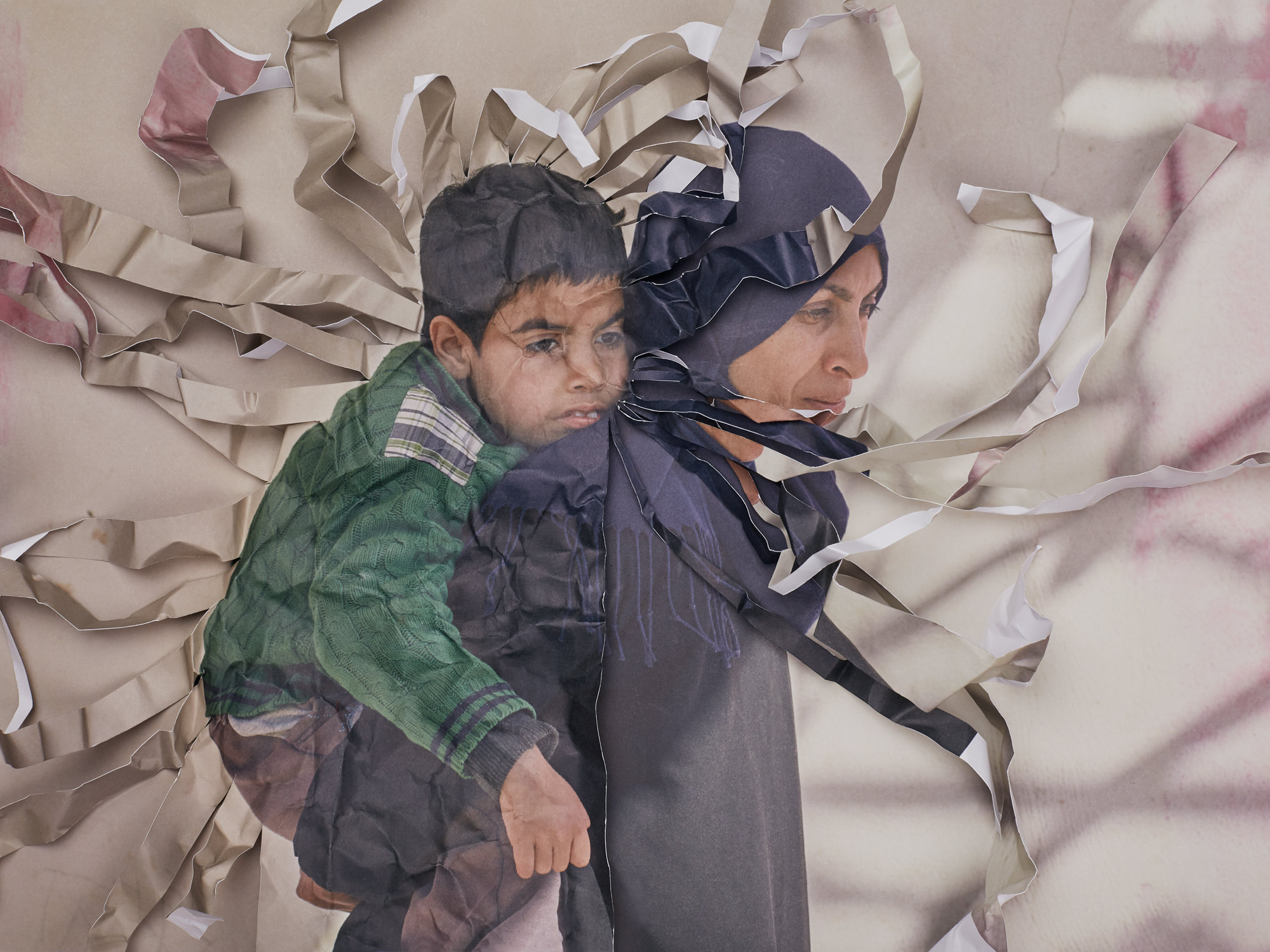

Abbas. Seven. & Adira. 30.

Abbas suffers from cerebral atrophy. When his parents and younger sister fled to Turkey from the Jordanian border, where they had lived in a camp after Isis invaded their home village, his mother and father had

to carry him every step of the way. The journey took 21 days. During the fighting, his mother, Adira, was unable to get hold of the medicine necessary to manage his condition. “I was in so much pain myself mentally and physically, but the hope of medical care for my son was all I wanted,” she told Sera Marshall and Sasha Nicholl of Save the Children. The family has yet to obtain its temporary protection registration from the Turkish government, so their access to healthcare and education remains limited.

Razan. Seven.

Razan’s father rode a motorbike. When she was very small, he used to take her and her little sister for rides, one in front of him and one behind. In 2012, her father was shot by a sniper. Later, her sister was fatally injured in the same bombing raid that killed their mother. Razan’s elder sister has become her principal carer, and has watched her regress: she wets the bed and finds it hard to tell the difference between reality and fiction. When Razan dreams of the future, though, it is simple: “I would love to be alone in a room. To be alone, have everything, and my home is always neat.”

*All names have been changed

Text by: Horiatia Harrod.

Portraits manipulation by Alma Haser using origami and paper techniques.